🦄 The Road Less Travelled

How some startups refuse the usual path of extreme-growth and aim for something else: profitability.

Welcome to the 52 new Fundraisedd people who have joined us since last Monday. If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed yet, join the Fundraisedd community now by clicking this here button:

Hi Friends,

Welcome to this week’s edition of Fundraisedd, the newsletter that tells you all you need to know about fundraising and startup finance. A special hello to the new subscribers who have joined the Fundraisedd community this past week 🙏🏻

Writing a pitch deck teardown about Buffer earlier this week, I discovered on Crunchbase they had only taken in $4M in financing. Trying to learn more about the terms and investors, I stumbled upon their corporate blog. I was aware Buffer was a successful company, but I didn’t know at what scale and how they got to where they are today.

As it turns out, they did so in a most unconventional way: they grew “slow” (VC-slow) and steady over the years.

Not only are they are a completely transparent corporation, giving out their real-time revenues, employee salaries, equity schemes, cost structure, everything is out there for anyone to read, but they also refused the growth at all costs traditional way of building a startup. More than that, they put their money where their mouth is, and bought out their Series-A investors to focus on profitability and slow down growth.

Focus on profitability? What a strangely refreshing concept in the startup world!

After 10 years of operations, Buffer “only” makes around $21M in ARR. With a profit margin of around 25% (according to their CEO), they make around $5.0-6.0M in profits each year while paying good salaries and incentivising employees with options.

This is the kind of success story that is not often featured in the media, and one that entrepreneurs should know more about.

We hear a lot about unicorn-valuation startups going public, having raked billions of dollars of losses over decades but very little about amazing, bootstrapped, profitable companies like Buffer.

That’s because these companies choose to walk a road less travelled. A road outside of the traditional way of doing business in the startup-verse.

But first, let’s understand the traditional way, the one that focuses on extreme growth at all costs.

And to understand it, we must understand the economics of a VC fund.

A VC fund economics

VC funds are usually structured around a pre-defined time horizon that can range from 7 to 12 years (until all investments are realised).

VCs have their preferred stages, industries, or geographies that they invest in. Within each vertical, their challenge is to spot the best deals, get them, and exit them at their expected return multiple.

They’re basically looking for a platinum needle in a gigantic haystack.

Their game is stochastic (I love this word) in nature: it can be analysed statistically but may not be predicted precisely. In other words, VCs have an overall idea of their chances of success and can, through their experience and market knowledge, estimate the chances of success of the startups they see, but they cannot precisely anticipate when, where, and how the success will happen before they invest.

This is why, when they have invested in a company, VCs aim for immediate and extreme growth: it’s the only way for them to safeguard their investment, and so for 3 reasons:

First, it’s always about the next liquidity event. VC investors expect the companies they invest in to set themselves up for their next round of financing. This implies not only defending your past valuations but also multiplying them at an ever-increasing pace. In this model, profits don’t matter. Top-line metrics are the drivers. Therefore, to achieve exponential growth in your valuation, you must achieve exponential growth in your revenues/user acquisition.

Second, companies must aim for an exit, be it an acquisition or an IPO. And this exit must reward all previous investors with a decent multiple. If all of them entered at valuations based on exuberant top-line growth metrics, you can’t slow down growth to increase profitability, as this would reduce your exit valuation compared to what was paid before.

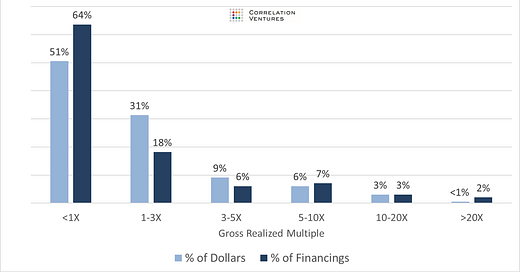

Third, it’s a numbers game. VCs invest in a portfolio of companies with an expectation that roughly 1/2 of the dollars they invest will lose them money (see chart below, courtesy of Correlation Ventures). They need to make up the losses with the remaining 1/2 and make great returns on basically less than 10% of their deals.

The probability of success is so low that VCs need an enormous increase in valuation from their top companies to have an acceptable expected return.

Assuming a standard 2/20 fee structure (without hurdle) and taking the mid-point of each range in the chart above, the expected return (E(r)) of a 7-year VC fund is 1.79x after fees or 8.6% per year.

If we take the lower value of each range (<1x being then 0), the E(r) of the fund after fees drops to 1.04x or 0.56% per year.

VCs need their top 0.05% dollars to return much more than 20x to succeed and make big money.

They need deals à la Peter Thiel x Facebook ($500k to $1B, 200x in 8 years) or à la Sequoia x WhatsApp ($60M to $3B, “only” 50x, but in 3 years!).

In that respect, it is understandable they would favour growth as the fundamental metric.

On an economics perspective, however, it often doesn’t make sense. Depending on your business model, extreme growth can be very costly.

Growth can be costly

As I’ve previously discussed in my analysis of SaaS Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), growth comes with a short-term increase in burn rate and induces a longer time to breakeven for SaaS companies.

The same can be said of platform-economics startups (think Uber or Airbnb). These companies spend enormous marketing budgets to acquire new users, but their usage patterns are unpredictable.

Contrary to a SaaS business, the payback period can range from days to years. There is no way to know. The only thing Uber can do, for example, is to provide users with an incentive to book a ride and hope it will work.

At the core, a broker’s business ought to be profitable from day 1 and require minimal capital expenditure. However, due to the pressure put on growth, these companies spend millions or billions on acquiring new users and on increasing transaction volume, even if they do it at a loss.

Uber actually admitted it in its S-1 filing before IPO:

We can choose to use incentives, such as promotions for Drivers and consumers, to attract platform users on both sides of our network, which can result in a negative margin until we reach sufficient scale to reduce incentives. — Uber S-1, p. 24 of the 3,286 total pages.

What makes them think that having reached a sufficient scale, they’ll be able to reduce incentives and aim for profitability?

Looking at their previous 6 years financials, the story is one of burnt capital in an economically inefficient company:

Sources: Uber S-1 filing, Yahoo Finance, Pitchbook. com

Over the years, Uber as accumulated over $21B in retained losses while its valuation reached a high of $75B+ in the private market.

Currently, Uber business model is still unsustainable. Moreover, any change in the legal framework of their key markets (drivers becoming employees or restrictions on use) could deal a terrible blow to the ride-hailing company.

The private investors who backed Uber actually made money on their investments at IPO, even if the company itself never did.

That’s what extreme growth gets you: an actual return for early-stage stockholders and investors even in the face of gigantic losses.

The road less travelled

Opposite this model, a few startups have decided to step out of this frenzied race and focus on what companies are supposed to be focused on: turning a profit.

To achieve this, they have made drastic decisions like voluntarily slowing growth, spending as little as possible on marketing, running lean operations outside of press coverage, and taking in as little external capital as possible.

I’d like to briefly introduce 4 of these companies today and describe what makes them so special.

Buffer

As I already mentioned in the introduction, Buffer is the company that got me started on this piece.

Buffer was founded in the UK in 2010 by Joel Gascoigne, Leo Widrich, and Tom Moor. It provides social media sharing automation tools and analytics to individuals and companies alike. With over 70’000 paid users the world over, Buffer ARR sits at around $21M per year at a 25% profit margin.

In particular, I was amazed by the CEO’s blog post on how Buffer decided to use nearly 50% of its cash reserve to buy out its Series-A investors to regain strategic control over his company.

They had already negotiated amazing terms for a Series-A, giving up 6.2% of the company at a $60M valuation with no board seats. Moreover, $2.5M of the $3.5M raised went to the founders and early employees, since they didn’t need the cash for growth.

You’ll notice this is a pattern among companies aiming for profitability from day 1: financing rounds tend to go towards rewarding employees.

Buffer’s buy-out offer was accepted by 67% of its Series-A investors, leaving the founders and employees with an 87% stake in the company, free to grow and develop as they wanted.

Buffer is a great example of a company that grew to an impressive yet reasonable size (once again, around 21M in ARR), generating profits, and making employees and shareholders happy in the process.

Atlassian

Atlassian was founded in Australia in 2002 by Scott Farquhar and Mike Cannon-Brookes. If you’re unfamiliar with their many products, Atlassian offers a suite of productivity and business tools for tech and non-tech teams like Trello, Bitbucket, Jira, Confluence, or Hipchat.

The corporate story is that the founders bootstrapped the company for many years using only a $10,000 credit card.

Atlassian was profitable from the start and never sought external investment for growth purposes. Accel invested $60M in Atlassian in 2010 through a secondary offering.

At the time, co-CEO Cannon-Brookes stated that they accepted the offer because as “they looked towards the long road to an IPO, Atlassian’s leadership decided it was time to build out its board of directors.” (Business Insider)

What fascinating is that not having external investors on board made it difficult for Atlassian to attract investors, even as a profitable and fast-growing company!

“People would look at us and say, “Oh, well how come you have no funding?” and “I’m not sure about this company …,” Cannon-Brookes says.

They also accepted it so that their employees could cash out:

Accel got the equity it wanted; Atlassian’s leadership didn’t give up control; Atlassian employees got to cash out their shares almost 5 years before the 2015 IPO; everybody was happy. And Atlassian never again took venture capital.

Atlassian accepted another $150M secondary market transaction with mutual-fund firm T. Rowe Price in 2014, valuing the company at $3.3B and once again, stockholders got to cash out with an amazing return.

Atlassian went public in 2015 and, ignoring the non-cash expenses related to a complex financing instrument, has been profitable ever since. Its current market cap sits at $51.5B.

Qualtrics

Founded by brothers Ryan and Jared Smith, with the help of their dad Scott, in Provo, Utah, in 2002, Qualtrics is a business intelligence company delivering market data insights to thousands of corporations around the world.

To quote a great Techcrunch article on the company’s history, quoting, in turn, Sequoia Capital partner Bryan Schreier, they are the “largest software company you haven’t heard of yet.”

Qualtrics is a family story. While being treated for cancer, Ryan’s dad had started working on a project that would become Qualtrics, and his sons helped him develop it. They first targeted academia as a market segment and built their presence through hustle and bustle.

Two years after its inception, they were making $100,000 per month. 3 years later, 1 million.

Qualtrics always avoided requests from the press and VCs alike, wanting to develop on their own terms without publicity. The article says that Ryan was turning down 3 VCs a day from 2010 onwards.

Eventually, in 2012, they accepted a $70M deal offered by… Accel Partners (and Sequoia Capital).

As Ryan said at the time:

One plus one has to equal five. If one plus one doesn’t equal five this deal doesn’t work. It has to be so compelling to achieve our objectives that we’re all in. We got Sequoia and Accel and that’s exactly what happened.

Once again, when your company is profitable and growing without external pressure, you find yourself in the exquisite position to choose your investors and dictate your terms. That’s comfort worth aiming for!

In 2019, it was announced that software-giant SAP had acquired Qualtrics for a whopping $8B.

Revolve

Following in Qualtrics footsteps, Revolve is, according to Fortune magazine, the “biggest, trendiest, most profitable e-commerce startup you’ve never heard of.”

Founded in 2002 by Michael Mente and Mike Karanikolas (the “Mikes”), Revolve is an online retailer of fashion clothing and accessories.

Born from the ashes of the dot-com bubble, the company was founded on the principle that it should not seek venture-capital funding.

As quoted in the Fortune article, Mente said:

Chasing revenue and growth without really understanding the guts of the business is something that venture capital will push you to do. We didn’t want to be at risk.

The article dates back to 2015, a year in which Revolve sold for $400M, roughly 3 times what UK competitor Farfetch sold that year ($142M). Farfetch was then valued at $1B. Revolve was basically unknown.

Hit hard by the Financial Crisis, Revolve had to resolve to outside investment but couldn’t find a match to its strategy and values in the VC world.

This is when they turned to private-equity firms and found TSG Consumer Partners. They invested $50M in Revolve in 2012, focusing on steady growth in all their verticals (women, men, and international sales).

Quoting once again from the article, the Mikes “believe Revolve can be a billion-dollar business in the next four or five years. Not a unicorn startup with a $1 billion valuation, mind you — a business with $1 billion in actual sales.”

Their focus isn’t on valuation, it’s on profitability.

As of October 2020, Revolve’s valuation sits at $1.3B and their 12-month trailing revenues at $600M.

They haven’t reached their $1B revenue target yet, but have profitable every year along the way on their own terms.

Conclusion

There is fundamentally no right or wrong way for your startup.

You need however to measure the implications of choosing one or the other.

The traditional path of VC financing and fast growth tends to create companies that accumulate losses and always need to find new investors at a higher valuation to continue fueling their operations.

While it is economically disputable, this model yields (for now at least) good results to both founders and investors, assuming the risk appetite of the market doesn’t diminish in the years to come.

The road less travelled is slower and, at times, probably much tougher. Without the comfort of regular cash infusions, bootstrapping is a difficult endeavour where financial awareness and business savvy are paramount.

It will, however, put you in a much better position to decide how you want your startup to evolve and where you want to go.

From the examples above, it also appears to be a model in which employees are well rewarded and, we can assume, lead happy professional lives.

The choice is yours, make sure you’re properly informed when you make it!

Thanks for reading, have a great week,

Nicolas

Suggested Reading

A strong take on Uber: Uber’s Path of Destruction — by Hubert Horan, in American Affairs

The Story Behind Qualtrics, The Next Great Enterprise Company — by Derek Andersen in TechCrunch

SAP Plans To Spin Out Qualtrics, Its $8 Billion Acquisition From 2018, For An IPO — by Alex Konrad in Forbes

Uber S-1 Filing, all 3,286 pages of it!

How Revolve Became the Biggest, Trendiest, Most Profitable E-commerce Startup You’ve Never Heard Of — by Erin Griffith in Fortune

The New Cool In The Startup World: SaaSy & Profitable — by Mary Ann Azevedo in Crunchbase News

Important article. Was a pleasure to read and see my own view confirmed by you.

One comment: “That’s because these companies choose to walk a road less travelled.” —> this road is not less travelled, it is the opposite, there are lot of companies who choose the sustainable entrepreneurship. It is only because of the noise in media about VC backed start-ups that we hear less about them. We hear less about them, but they are not less;-)